Water and PFAS Regulations

Water Regulations in the U.S.

To protect public health and safety, the U.S. federal government established these notable acts:

- The Clean Water Act (CWA) of 1972 set limits on pollutant discharges from industrial and wastewater facilities.

- The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) of 1974 allows the EPA and states to set standards for how water is distributed safely to the general public.

Both laws provide guidance for using the best available, affordable technologies to limit the spread of harmful compounds into our water supply.

The SDWA currently provides National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) and Maximum Contaminant Limits (MCLs) for over 80 compounds that could be potentially found in drinking water, such as:

- inorganic chemicals (e.g., arsenic, copper, fluoride)

- organic compounds (e.g., benzene, styrene, vinyl chloride)

- microorganisms

- disinfection byproducts (DBPs)

NPDWRs are federally enforceable limits that apply to all public water systems in the US. Here are the requirements municipal water utilities must meet.

Final PFAS Drinking Water Regulations

PFAS (Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances) are a large group of man-made chemicals that have been used in a variety of industrial and consumer products since the 1950s. Also called “Forever Chemicals”, these substances are made up of strong carbon-fluorine bonds which do not easily break down over time. Scientific studies have suggested that exposure to PFAS is linked to adverse health effects such as increased risk of certain cancers, reduced liver function, reproductive harm, and damage to the immune system. One source of PFAS exposure is through the water we drink.

In April 2024, the EPA released the Final PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation, which established legally enforceable limits (Maximum Contaminant Levels, or MCLs) for six PFAS compounds. PFOA and PFOS both have an MCL of 4.0 ppt (also expressed as ng/L). PFHxS, PFNA, and HFPO-DA (commonly called Gen-X) each have an MCL of 10 ppt. Any mixtures containing two or more of PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, and PFBS, may not exceed a Hazard Index of 1. The Hazard Index is a unitless coefficient that factors in each compound’s toxicity with their concentration as a combined MCL-type limit. The most up-to-date information and resources on PFAS regulations can be found on the EPA’s website.

Organizations such as the American Water Works Association and Water Research Foundation have conducted several studies and provided guidance on meeting compliance. For example, a Case Study at the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority in Wilmington, NC compares the best available technologies in a full-scale implementation. The EPA has released a report to help utilities estimate the costs of implementing granular activated carbon.

The EPA has identified activated carbon as one of the best available technologies for the removal of PFAS. It will be essential for achieving widespread compliance with these regulations across communities large and small.

Compliance Timeline

Public water systems (PWSs) will be required to comply with the new regulations in a series of phases over the next five years.

By 2027: PWSs must complete initial monitoring requirements (see section below)

Starting 2027: PWSs must begin ongoing compliance monitoring (see section below) and must make the public aware of the PFAS levels in their drinking water.

By 2029: PWSs must implement PFAS treatment solutions if their levels exceed the MCLs.

Starting 2029: PWS must comply with the PFAS MCLs and must notify the public if an MCL is violated.

Initial Monitoring Requirements

To ensure safe drinking water for each community, the existing monitoring requirements should be amended to include all the regulated PFAS compounds. For example, current monitoring for synthetic organic compounds (SOCs) should now measure PFAS compounds as well.

All surface-water and groundwater systems serving more than 10,000 people must monitor for the regulated PFAS compounds quarterly within the first 12-month period. To limit expenses, they can use previously obtained samples to satisfy the initial monitoring requirements based on final ruling terms. Like previous SOC rules, sampling points are at any entry point to the distribution system (EPTDS) being served. If PFAS levels are below the triggering point (i.e., 1/3 the MCL of each compound), monitoring frequency may be reduced, based on the size of the system and population served.

Ongoing Monitoring

Systems serving 3,300 or fewer customers that do not detect regulated PFAS in their systems at or above the rule trigger level (1.3 ppt for PFOA and PFOS and 0.33 for the HI PFAS (PFHxS, HFPO–DA, PFNA, and PFBS)) must analyze one sample for all regulated PFAS per three-year compliance period.

For systems serving more than 3,300 people, systems that do not detect regulated PFAS in their systems at or above the rule trigger level (1.3 ppt for PFOA and PFOS and 0.33 for the HI PFAS (PFHxS, HFPO–DA, PFNA, and PFBS) must analyze two samples for all regulated PFAS at least 90 days apart in one calendar year per three-year compliance period.

Either way, sampling must be done at each EPTDS that does not meet or exceed the rule trigger level.

Monitoring Requirements

Initial monitoring requirements depend on the type and size of system. For all surface water systems and groundwater systems serving fewer than 10,000 customers, monitoring must be conducted quarterly within a 12-month period with samples collected 2-4 months apart. For groundwater systems serving more than 10,000 customers, monitoring must be conducted twice within a 12-month period with samples collected 5-7 months apart. To reduce expenses, PWSs may be able to use previously obtained samples to satisfy some or all of the initial monitoring requirements. Sampling points are at all entry points to the distribution system (EPTDS) being served.

The requirements for a PWS’s ongoing monitoring are dependent on the results of the initial monitoring. If PFAS levels are below the triggering point (i.e., 1/2 the MCL of each compound) in all samples, monitoring frequency is reduced to once every 3 years. However, if any sample is above the triggering point, the default quarterly monitoring must be conducted at that entry point. EPA has published a detailed fact sheet explaining monitoring requirements.

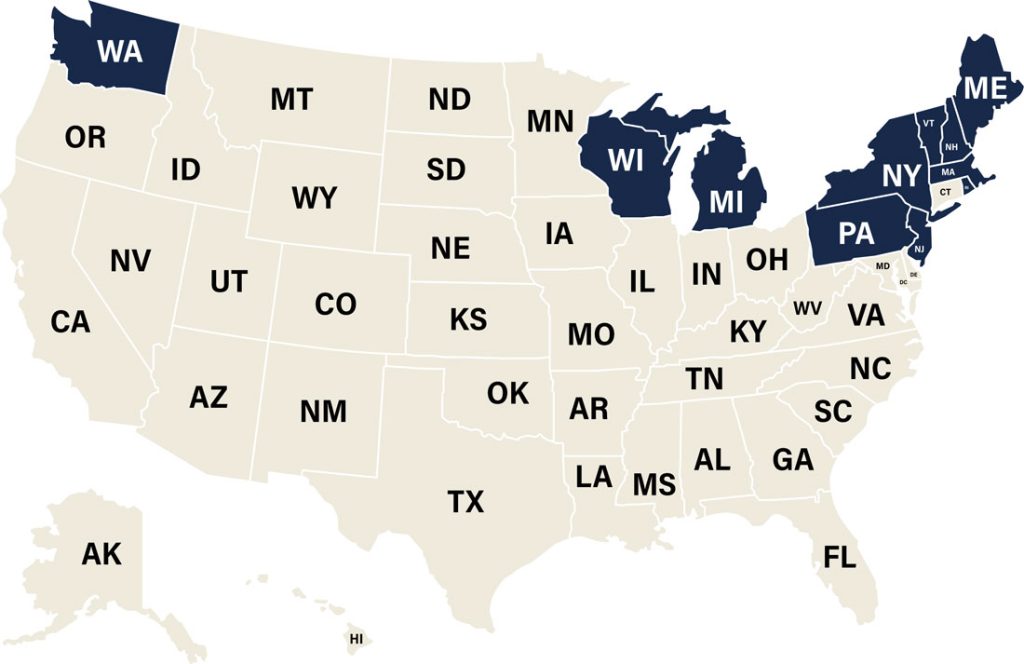

State-level PFAS Regulations

Beyond the proposed federal EPA rules, 11 states already have implemented PFAS regulations:

- Maine

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New York

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- Vermont

- Washington

- Wisconsin

Delaware and Virginia are currently developing PFAS regulations. PFAS guidance levels and/or health advisories have been implemented in twelve additional states (Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, North Carolina, New Mexico, Ohio, and Oregon).*

*Source: Saferstates.org; April 2024